Why Won't PostgreSQL Use My Covering Index?

Dear Postgres, Why won’t you use my covering index?

Lately I’ve been learning to tune queries running against PostgreSQL, and it’s …

Read MoreIndex bloat in Postgres can cause problems, but it’s easy to miss.

I’ve written about how vacuum problems can prevent PostgreSQL from using covering indexes, and index bloat is one of the things that can make vacuum struggle.

Here’s what you need to know about index bloat, how to find it, and how to fix it.

“Index bloat” describes an index that takes up significantly more space on disk than it actually needs. This occurs because Postgres stores indexes in 8 KB fixed-size pages which can accumulate empty space over time.

When you delete or update rows, the old index entries become “dead tuples”—they’re no longer valid, but they remain on the page taking up space. Vacuum marks that space as available for reuse, but it doesn’t compact the pages themselves. You end up with pages that have a lot of empty space scattered throughout them.

Index bloat accumulates through normal database operations:

To reiterate what’s mentioned above (it’s a common misunderstanding): autovacuum removes dead tuples from tables and marks space in indexes as available for reuse, but it doesn’t reclaim space in indexes.

When you have significant index bloat, vacuum has to work harder. Vacuum needs to scan indexes to find and remove references to dead tuples. If your indexes are bloated, they contain more pages because the pages aren’t compacted—an index that should be 10 GB might be 15 GB or more instead if bloat gets bad, and imagine how this expands for larger indexes. Vacuum has to scan through all the extra pages, which takes more time and consumes more CPU and IO resources. The more bloat, the more pages to scan, and the longer vacuum takes.

In systems with heavy write workloads, this can create a vicious cycle: vacuum runs slowly because of bloat, which means it can’t keep up with new dead tuples, which creates more bloat, etc.

I’ve seen cases where vacuum was taking hours on tables that should have been much quicker to vacuum, all because the indexes were severely bloated.

AWS provides a useful script for calculating index bloat percentage in RDS PostgreSQL instances: Rebuilding indexes. This script calculates bloat_pct for each index and helps you identify which indexes need attention.

The script compares the actual index size to the expected size based on the number of tuples, giving you a percentage of bloat. AWS recommends running REINDEX when the bloat percentage is greater than 20%, but let your conscience be your guide.

Postgres supports online index rebuilds using REINDEX CONCURRENTLY. Under concurrent mode, the index remains available for reads and writes during the rebuild operation. The PostgreSQL documentation explains that REINDEX CONCURRENTLY builds a new index alongside the existing one, performs multiple passes to capture changes made during the rebuild, then switches constraints and names to point to the new index before dropping the old one. This process takes longer than a standard rebuild but allows normal operations to continue throughout.

Here’s the syntax:

REINDEX INDEX CONCURRENTLY index_name;Or for all indexes on a table:

REINDEX TABLE CONCURRENTLY table_name;The CONCURRENTLY keyword makes it online. Without it, REINDEX takes an exclusive lock on the table, blocking all access.

If a REINDEX CONCURRENTLY operation fails partway through, Postgres leaves behind an “invalid” index that you can’t use. According to the PostgreSQL documentation, when REINDEX CONCURRENTLY fails, Postgres leaves behind a temporary index with a name ending in _ccnew. This index won’t function for reads (but still has overhead for updates), so drop it before trying the rebuild again.

You can find invalid indexes by looking for indexes whose name ends in %_ccnew:

SELECT

schemaname,

indexname,

indexdef

FROM pg_indexes

WHERE schemaname = 'public'

/* Concurrent rebuilds create temporary indexes named like this */

AND (

indexname LIKE '%\_ccnew'

OR indexname NOT IN (

SELECT indexrelname

FROM pg_stat_user_indexes

)

);Or query the pg_index, pg_class, and pg_namespace system catalogs to find indexes marked as invalid:

SELECT

n.nspname AS schema_name,

c.relname AS index_name,

pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size(c.oid)) AS index_size

FROM pg_index i

JOIN pg_class c ON i.indexrelid = c.oid

JOIN pg_namespace n ON c.relnamespace = n.oid

WHERE NOT i.indisvalid

AND n.nspname = 'public';If you find invalid indexes from a failed concurrent rebuild, drop them before trying again. You can use DROP INDEX or DROP INDEX CONCURRENTLY:

DROP INDEX CONCURRENTLY schema_name.invalid_index_name;The CONCURRENTLY keyword avoids blocking by not requiring an ACCESS EXCLUSIVE lock on the table.

Here’s a script you can use on a test database to create and observe index bloat.

CREATE EXTENSION IF NOT EXISTS pgstattuple;

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS test_bloat;

CREATE TABLE test_bloat (

id integer PRIMARY KEY,

user_id integer NOT NULL,

order_date date NOT NULL,

status_code integer NOT NULL

);

CREATE INDEX idx_test_bloat_multi ON test_bloat (user_id, order_date, status_code);

/* Insert some sample data */

INSERT INTO test_bloat (id, user_id, order_date, status_code)

SELECT

generate_series(1, 1000000),

(random() * 10000)::integer,

CURRENT_DATE - (random() * 365)::integer,

(random() * 10)::integer;

/* Check index size and empty space on pages */

SELECT

s.schemaname,

s.indexrelname AS indexname,

/* Total size of the index on disk */

pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size(s.indexrelid)) AS index_size,

/* Total number of pages: leaf pages + internal pages + empty pages + deleted pages */

(stats.leaf_pages + stats.internal_pages + stats.empty_pages + stats.deleted_pages) AS total_pages,

/* Average density of leaf pages (0-100, lower = more empty space on pages) */

ROUND(stats.avg_leaf_density::numeric, 1) AS avg_leaf_density,

/* Empty space on leaf pages based on current density */

/* If density is 50%, then 50% of leaf page space is empty */

pg_size_pretty(

(

stats.leaf_pages * current_setting('block_size')::bigint *

(100.0 - stats.avg_leaf_density) / 100.0

)::bigint

) AS empty_space,

/* Percentage of space on leaf pages that's currently empty */

ROUND(

(100.0 - stats.avg_leaf_density)::numeric,

1

) AS empty_space_pct

FROM pg_stat_user_indexes AS s

/* Use pgstatindex() to get actual page-level statistics from the index */

CROSS JOIN LATERAL pgstatindex(s.schemaname || '.' || s.indexrelname) AS stats

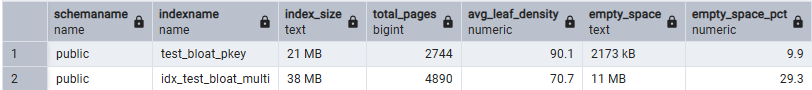

WHERE s.relname = 'test_bloat';Here’s the initial size and density - the primary key pages are 90.1% full, the multi column index pages are 70.1% full.

/* Delete a large portion of rows */

DELETE FROM test_bloat WHERE id % 2 = 0;

/* You can recheck the size using the query above, but nothing will

be different until you run VACUUM. */

/* Run VACUUM ANALYZE */

VACUUM ANALYZE test_bloat;

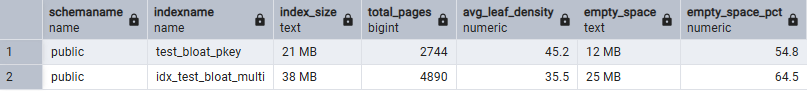

/* Recheck the size using the query above */Now here’s our index size and empty space: the primary key pages are 45% full and the multi column index pages are 35.5% full.

/* Rebuild index concurrently to reclaim space */

REINDEX INDEX CONCURRENTLY idx_test_bloat_multi;

REINDEX INDEX CONCURRENTLY test_bloat_pkey;

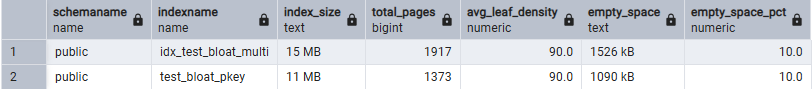

/* Recheck the size using the query above */Here’s the size and empty space after rebuilds: each index is 90% full.

/* Clean up */

DROP TABLE test_bloat;Have you checked your indexes for bloat? Have you implemented automated maintenance for bloat?

Copyright (c) 2025, Catalyze SQL, LLC; all rights reserved. Opinions expressed on this site are solely those of Kendra Little of Catalyze SQL, LLC. Content policy: Short excerpts of blog posts (3 sentences) may be republished, but longer excerpts and artwork cannot be shared without explicit permission.